Church History Introduction

Church HistorySteve Gregg

In this introduction to church history, Steve Gregg emphasizes the importance of studying the history of Christianity in order to gain a greater perspective on the body of Christ, which extends beyond our own time and place. He acknowledges the shortcomings of institutionalized Christianity throughout the centuries, but also notes the divine origins of the church and the importance of maintaining a personal relationship with God. Rather than conforming to strict patterns of belief or institutionalized leadership, Gregg encourages believers to focus on the core teachings of Jesus and to allow for differences of conviction and interpretation within the community of faith.

More from Church History

2 of 30

Next in this series

The Very Beginning

Church History

In "The Very Beginning," Steve Gregg explores the early days of the Christian church and its relationship to the Jewish synagogue. He notes that while

3 of 30

Passing the Torch

Church History

In "Passing the Torch," Steve Gregg discusses the apostolic period of the church, emphasizing the work of the Holy Spirit and the formation of the bod

Series by Steve Gregg

Judges

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Book of Judges in this 16-part series, exploring its historical and cultural context and highlighting t

Romans

Steve Gregg's 29-part series teaching verse by verse through the book of Romans, discussing topics such as justification by faith, reconciliation, and

Biblical Counsel for a Change

"Biblical Counsel for a Change" is an 8-part series that explores the integration of psychology and Christianity, challenging popular notions of self-

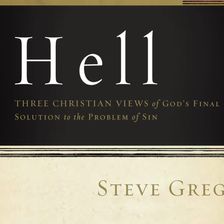

Three Views of Hell

Steve Gregg discusses the three different views held by Christians about Hell: the traditional view, universalism, and annihilationism. He delves into

The Holy Spirit

Steve Gregg's series "The Holy Spirit" explores the concept of the Holy Spirit and its implications for the Christian life, emphasizing genuine spirit

Gospel of John

In this 38-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Gospel of John, providing insightful analysis and exploring important themes su

Creation and Evolution

In the series "Creation and Evolution" by Steve Gregg, the evidence against the theory of evolution is examined, questioning the scientific foundation

The Jewish Roots Movement

"The Jewish Roots Movement" by Steve Gregg is a six-part series that explores Paul's perspective on Torah observance, the distinction between Jewish a

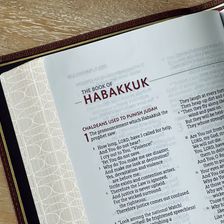

Habakkuk

In his series "Habakkuk," Steve Gregg delves into the biblical book of Habakkuk, addressing the prophet's questions about God's actions during a troub

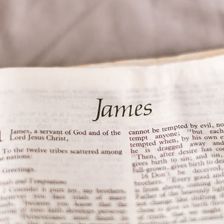

James

A five-part series on the book of James by Steve Gregg focuses on practical instructions for godly living, emphasizing the importance of using words f

More on OpenTheo

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

Why Is It Necessary to Believe Jesus Is God?

#STRask

February 19, 2026

Questions about why it’s necessary to believe Jesus is God, whether belief in the Trinity is required for salvation, and why one has to believe in the

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God